heated rivalry

& the sensory pleasures of looking

look!

My villain origin story, if there ever was one, is probably related to the egregious overuse of feminist film scholar Laura Mulvey’s notion of the ‘male gaze,’ in popular discourse. The concept is first articulated in Mulvey’s seminal 1975 essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,’ which draws on Freud and Lacan to peel apart the dynamics of spectatorship in film. It’s a weird essay, full of castration anxiety and phallocentricity and all of the ooey gooey psychoanalytic stuff that I have a hard time buying and a hard time staying away from when thinking about media.

The gist of it is that Mulvey is interested not just in the gazes of characters within the content of a film, but the gaze of the viewer or audience member upon the film. She references the Freudian notion of scopophilia, or a desire to look or observe, especially at a thing you aren’t permitted to see, in order to make sense of the role of a spectator. Crucially, Mulvey asserts that heterosexual men, as viewers and makers of a film and as members of a dominant class, are able to subject women on screen to their gaze, rendering women as passive, sexualized, flattened objects within a film narrative and, by extension, within a society. Where men in film are allowed to act, to change, and to drive the action of a narrative, women are relegated to producing visual spectacles.1

It’s hard to overstate how formative this essay was in the subsequent five decades of media studies, film studies, and philosophy. Numerous extensions and critiques of Mulvey’s work have been offered since: Black scholars in particular, have named the complicated racial dynamics of viewership that go undiscussed in the essay; queer scholars have written at length about the complexities of gazing as a queer person, which displaces and reshapes the patriarchal order accepted implicitly by the essay. Related concepts like the colonial gaze, the white gaze, or the oppositional gaze flooded academic publishing as a result. Everywhere, theorists were profoundly influenced by Mulvey’s suggestion2 that the act of gazing constituted oppressive assertion of power, or mastery, over the object being looked at.

Mulvey’s work is a load-bearing pillar of media analysis and feminist theory, but like other highly influential pieces of feminist writing3, the concepts have become popular enough to breach containment and take on a decidedly “feminish”4 flavor. With every passing day, the ‘male gaze’ has taken on a bland, tired spin wholly disconnected from the 1975 piece that gave it life.

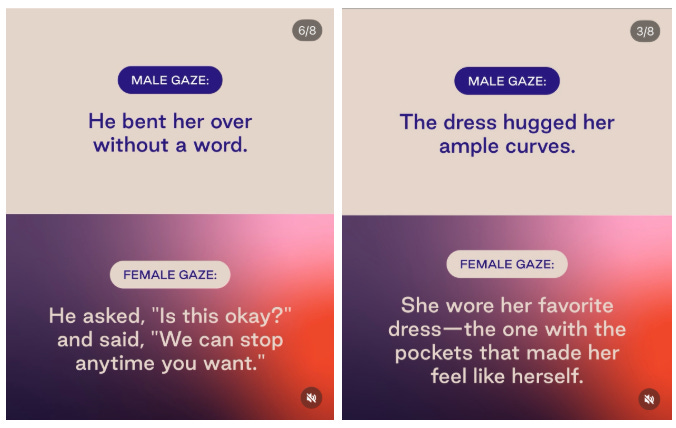

‘Male gaze,’ these days, seems to be shorthand for “when men look at things,” or perhaps “when men do things,” or maybe just “when men.” It’s a horribly essentialist, uncreative point of view that doesn’t allow for the possibility that gender socialization isn’t fixed and incontrovertible, but cumulative, evolving, always in flux.

Worse, still, the concept has reached a saturation point where Mulvey’s ‘male gaze’ has become, maybe, the only way to think about the act of “gazing,” at all. Never mind that Foucault and Lacan and Freud and Kristeva and about a billion other writers have wrestled with different ways to think about the gaze forever.

regard!

A few months ago an enormously popular adult film actor left a really thoughtful comment5 on my Frankenstein (2025) review and it led me to her TikTok page. She’d just 6 posted an equally thoughtful reflection on 10 years of being a ‘mattress actress,’ a job that she said required her to be an “empty vessel,” for the projections of other people, but also granted her the skill to look at other people, her scene partners or the camera, as if they are enough. To see the yawning desire in another person to be seen as worthy or deserving of intimacy or closeness and grant it by virtue of her gaze and attention alone. It’s a skill that became transferrable. She spoke beautifully about regarding her sister, her mother, the other people in her life with the sense of “enough-ness,” she’d previously only performed on camera.

The phrasing really struck me. Any therapist-in-training could tell you that a core competency in clinical training is the mastery of what humanist psychologist Carl Rogers referred to as unconditional positive regard, or the ability to see another with complete openness and non-judgment. It is one of the easiest, hardest, and loveliest part of therapy, and its effect can be profound in both directions, for therapist and client. I know it. I’ve felt it. I see it all the time. The way we look can be deeply life-giving, connective, animating, for both observer and observed.7

It’s one of the reasons why I have a hard time believing that the act of gazing is, necessarily and exclusively, subjugating. Aren’t there other ways to gaze?

Interestingly, Lacan conceives of the gaze as the object in the visual field, rather than the act of looking itself. Philosopher Todd McGowan, interpreting Lacan, contends that the gaze is a marker of our “non-neutrality,” or the “point at which the subject’s desire warps the image.” The gaze is a distortion of what is presented in our visual field, the point at which something takes on extra significance.8

Romance novels understand this keenly. Take this line from The Luckiest Lady in London, by the inimitable Sherry Thomas:

She was recovering from a case of sniffles brought on by a sudden onslaught of autumnal weather. Her nose was red. The rest of her face, too, was somewhat ruddy. And the somber blue of her cloak did her complexion no favors, making her appear even more splotchy.

All this Felix perceived. But he could see only loveliness, endless, endless loveliness.

Love was not blind, but it might mimic a deteriorating case of cataracts.

The narrator, Felix, is a Machiavellian prince struck down in his prime by deep adoration for his own wife— embarrassing! His assessment of her appearance is clinical at first, an evaluation of the weather, the colors of her skin, the attire she wears. It all gives way, however, for the thing that he actually sees. Her loveliness, endless, endless loveliness. Sherry Thomas illustrates, here, how distortions to a narrator’s visual environment are some of the first, most powerful ways for a romance writer to begin scaffolding a romantic connection for a reader. If love is “favoritism par excellence,”9 then the senses are the entrypoint into that favoritism, selective attention, that distorted experience of the world.

In Heated Rivalry (TV), it’s Shane Hollander’s look at Ilya Rozanov in the very first seconds of the show that tip us off to the connection between the two of them. Shane reaches out once to shake Ilya’s hand. Then twice. It’s a far cry from his typical expression, where he’s often spotted looking vaguely off into the middle distance. Ilya eats up his visual frame, distorts his vision so completely that no one else— not Rose, not any other man— can be anything but set dressing. In the book’s take on the same scene, Ilya looks at Shane and gets caught: “His skin, however, was flawless. Distractingly so. Smooth and tan with— and this was his most striking feature— a smattering of dark freckles across his nose and cheekbones.” It’s a level of sensory detail and attention we’ve yet to see in his perspective until that point, the exact moment where Ilya’s budding desire for Shane warps the image.

Lacan’s notion of the gaze offers something different from Mulvey’s formulation: that the gaze is the point where we lose or cede authority or mastery or power over the subject of viewing. It’s the point where we realize that we can’t assert control over our visual field, that our visual field takes on meanings and distortions and shapes that exist because of us. More specifically, because of something within us that is unconscious, unknowable, and beyond our grasp. We can’t know why Ilya is obsessed with Shane’s freckles, why this particular beautiful man compels him in a sea of beautiful, muscly men. All we know is that he does, and that it changes him forever. 10

spectate!

In one of my favorite parts of the Heated Rivalry press tour, Hudson Williams was asked about his familiarity with the source material before auditioning for the part11:

I wasn’t even very familiar with how these women-catered romance genres, how fucking vulgar they are. Not in a bad way, by any means, but they get into it. They get so nasty and so descriptive. It’s beautiful, I love it.

His use of “vulgar,” really charmed me, as has Jacob Tierney’s declaration in an interview that the Heated Rivalry books “are porn.”12 To call a romance novel vulgar and pornographic is, by all accounts, indication of the speaker’s disapproval and disdain for the genre, but few people who’ve followed Tierney and Williams online or watched Heated Rivalry could accuse them of that. In fact, Tierney and Williams seem to have hit on something deeply honest about romance.

It’s a frequent point of defensiveness from within romance that romance isn’t porn.13 I’ve written before about the SWERF-iness of this sentiment14 before, but it’s also worth noting that there are elements of romance that are pornographic. In episode 1 of Heated Rivalry, there’s a scene where Shane gets on his knees and blows Ilya . It’s a great scene - it’s the first time Shane has sex with a man. It’s the exchange that sets the tone for the next several years of their sexual relationship. You can, quite literally, hear the slurping noises.15 There’s a scene in episode 6 where Ilya blows Shane and someone on Twitter described it as Ilya “bobbing for apples.” It’s one of the most playful, easy moments of sexual chemistry in the show, evidence of their growing intimacy, the comfort of their relationship, and it’s also doing all kinds of interesting work for Shane, a character with a begrudging fondness for exhibitionism.16 These scenes are explicit, unveiled, and also really fucking hot.

That the show is willing to present the sensory pleasures of sex to a viewer has opened it up to significant scrutiny. Publication after publication has released its own point of view on the overt sexuality of the show, wavering somewhere between frank appreciation and dismissiveness. It speaks, in part, to the intense sexual conservatism of our time compared to even the recent past. In part, it speaks to a lack of understanding of genre fiction itself.

In Vulgar Genres: Gay Pornographic Writing and Contemporary Fiction (2021), Steven Ruszczycky, articulates what has been culturally understood as the key distinction between pornography and literature:

Where [literary writing] engaged the reader in the disinterested contemplation of beauty, [pornographic writing] turned one’s attention toward the self-interested pleasures of the flesh. Beyond being mere description of particular textual properties, the distinction between literature and pornography also served the ideological ends of class differentiation… (p.2)

In effect, serious literature traffics in the figurative, where genre literature traffics in the visceral, the literal. This distinction is drawn along classed, gendered lines. Pulpy magazines for the poor, the unsophisticated, the naive, the sentimental. Hard bound classics for the wealthy, the elite, the cultured, the cerebral. The distinction is, for many romance readers, rightly understood as derogatory. The defensiveness that springs from it isn’t unsubstantiated.

But we have to remember that romance is vulgar. It is base to watch a show where you can hear blowjob noises in the first episode. It is pornographic to watch a man spit into the palm of his partner so they can lube up for sex. These scenes are intended to arouse and titillate and excite. And there is such tender, full beauty to be found in vulgarity. Our tendency to immediately grant vulgarity a negative valence speaks to our own aversion to the body and its animality.

The body is disgusting, filthy, messy. Sex is vulgar and base. So what? Who do we serve by pretending that nastiness isn’t (1) narratively useful, powerful, and compelling; (2) honest?

watch!

I’m sure, like me, you’ve seen the discussions online of the epidemic of cishet women fetishizing masses of gay men for sport.17 Even before Heated Rivalry burst onto the scene, this was a constant topic of discussion in M/M romance spaces, but the astronomical popularity of the show seems to have pushed this line of thinking back into the foreground. The idea that women may derive pleasure from watching men be intimate with each other seems, in a uncanny extension of the ‘male gaze’ discourse, tied unavoidably to objectification, subjugation, and dehumanization. Never mind that one of the most engaged viewerships of the show is lesbians.18 Never mind that even ostensibly cishet individuals can have deeply complex relationships with gender, sexuality, and embodiment. Never mind that this is an interesting story even for people like me, who don’t usually read or watch M/M at all.

The reality is still that we are ill-equipped to see the gaze as anything but violent and oppressive. We are equally ill-equipped to see desire and pleasure as anything but violent and oppressive.

It’s getting harder to ignore that everywhere I look, people are finding themselves suspicious of the body and sensory pleasures derived from it. Every embodied experience becomes evidence of pathology, violence, bad faith, degradation. To look and enjoy is necessarily voyeuristic. To perform is necessarily exhibitionistic and narcissistic. To be vulgar is to be déclassé. Maybe by virtue of the fact that I spend a lot of time online in the digital sphere where nothing is real and everything is important, the realm of the physical seems to be receding further and further into the periphery to make way for absolutely nothing at all. No mess and, relatedly, no meaning.

The idea that the pleasures of the flesh are mutually exclusive from meaningful contemplation is the product of a world that wants badly for us to self-alienate. Truthfully, figuring out what I find pleasurable, beautiful, hot, worth looking at has been one of the most fruitful projects in my life. The distortions in my visual field force me to surrender to the unknowable thing in me, that opaque entity that sees two people fall in love and says, every time, “Yes, that. More of that.”

I really liked this video essay and this follow-up essay about the topic! This New Yorker piece was also lovely. Also, full reference for Mulvey:

Laura Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Screen, Volume 16, Issue 3, Autumn 1975, Pages 6–18, https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6

well, Foucault’s suggestion first, really.

i’m looking at you, Dr. Crenshaw.

This is a reference to a piece by literary critic Merve Emre on “Mom Rage”: “It is a measure of how influential such theorizing has become that this proposition, once radical, is almost received opinion among a new crop of cultural critics. But, by the same token, the newer books—call them “feminish”—engage only sparingly with the original sources. Reading paraphrases of paraphrases of paraphrases, one starts to feel as if there is something a little hollow and shiftless about the ease with which phrases such as “white supremacist, homophobic, classist, ableist, xenophobic, transphobic, misogynistic, capitalist patriarchy” are trotted out. We get the right words, strung together like marquee lights, but not the structural analysis that puts them in relation to one another.”

one of the only thoughtful comments, if we’re being real

You may not be able to see this if you don’t have a login; her profile is PG-13 from what I can see, but she’s still age-restricted I think? So I’ve tried to summarize it faithfully

Iris Murdoch also explores this in her notion of a “just and loving gaze”

This video essay was so great:

this is Becca Rothfeld’s All Things are Too Small

Really loved Kelly Oliver’s piece ‘The Look of Love,” (2001) on this; she argues that Lacan still sees the gaze as alienating, but draws on Irigaray and others to talk about how the gaze helps us understand where we end and the other begins. Facilitates our affection for the other as something connective, rather than alienating.

Interview in Hollywood Reporter

in my first issue of romance discoursing

an inspiration to foley artists everywhere <3

Talked about this on TikTok/Reels first; I’m interested in the illustration of self-commodification (advertising darling), exhibitionism (show off!), self-objectification and eventually disordered eating (in The Long Game) in Shane.

I really love this, especially what you’re saying about people only seeing desire/pleasure as violent/oppressive. I read a ton of both romance and literary fiction, and I understand where the defensive “it’s not porn” attitude is coming from for romance readers, for sure, especially when the genre and its fans are so openly disparaged, but I’ve always sort of felt like if you’re arguing that graphic sensuality and depictions of sex INTENDED to arouse and titillate you aren’t vulgar/porn, maybe you’re not reading it right! At the very least, you’re negating the value of pleasure as art by trying to sweep that part of it under the rug. But there’s so much shame, right? So much of the argument comes from shame surrounding the admittance that something brings pleasure at all!

yes yes to all this and especially:

‘It’s one of the reasons why I have a hard time believing that the act of gazing is, necessarily and exclusively, subjugating. Aren’t there other ways to gaze?’

almost as if people refuse to believe we can be participants in being gazed upon.